Let me tell you about something happening right now.

Artificial intelligence is reshaping the global economy. But not in the way most people think.

This is not about machines taking jobs. This is about how institutional structures determine whether AI amplifies inequality or reduces it.

The Numbers Are Not What They Seem

The IMF tells us that AI will impact almost 40% of jobs worldwide. That sounds dramatic. It is dramatic.

But here is the part people miss: This 40% breaks down very differently across the world.

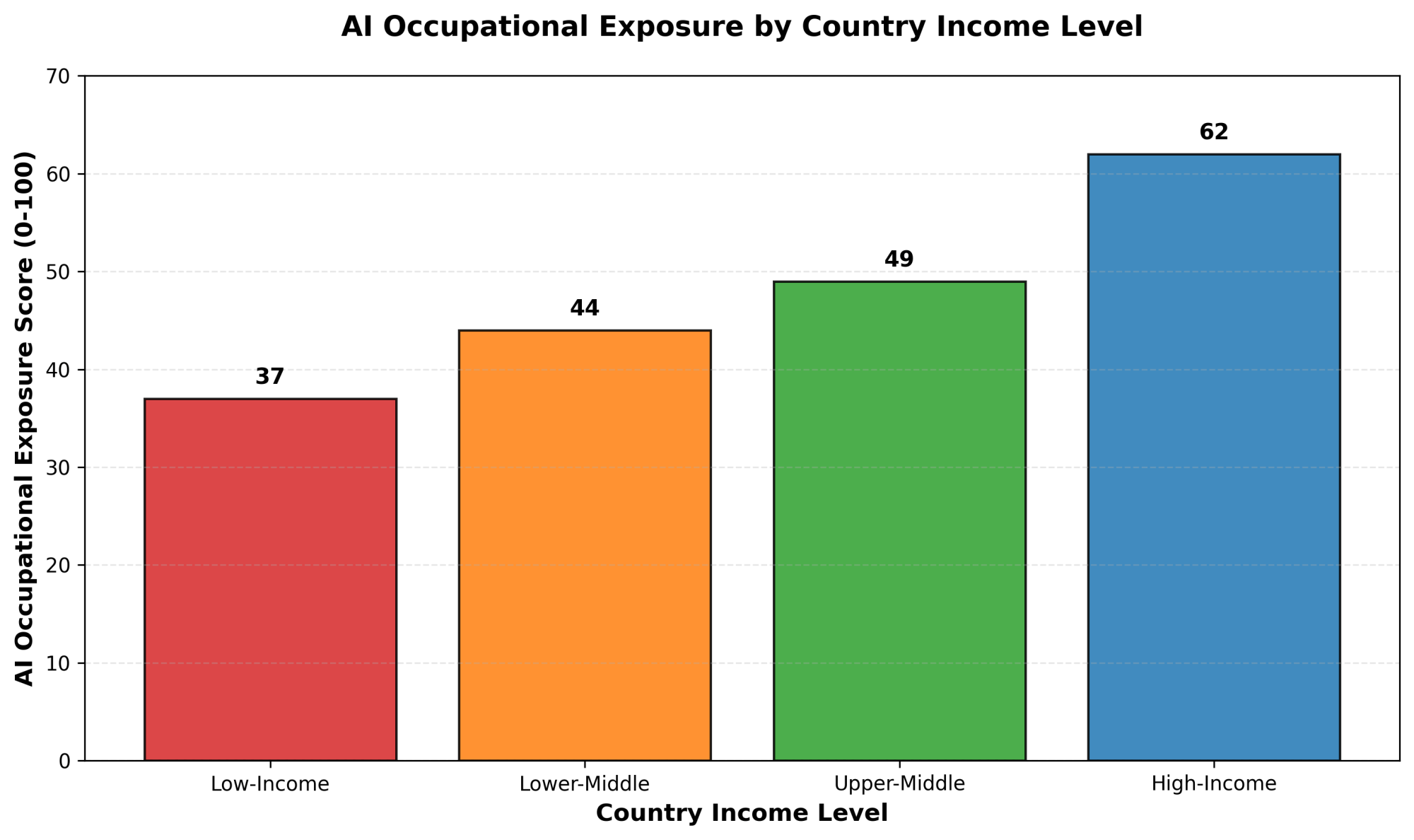

In advanced economies, the exposure is 60%. In emerging markets, it is 40%. In low-income countries, only 26%.

You might think lower exposure is good news for poorer countries.

It is not.

Lower exposure means these countries have fewer opportunities to benefit from AI. Their institutional structures, their digital infrastructure, their human capital — all of these are not ready. The World Bank data in 2025 shows this clearly when we look at AI occupational exposure scores:

Source: World Bank (2025)

The gap is structural. Not temporary.

What AI Actually Does to Workers

Here is how the traditional story goes: Automation affects low-skilled workers. High-skilled workers are safe.

AI is different.

Unlike previous automation waves that targeted middle-skilled workers, AI’s displacement risks extend to higher-wage earners. The IMF found this in 2024. But these same high-income workers also have higher potential for complementarity with AI. They can work with AI. Their productivity increases. Their wages go up.

Lower-skilled workers? They get productivity gains too. Some studies show generative AI helps them significantly. But the redeployment risk — the chance they will need to change occupations entirely — is 3 to 14 times higher than for high-wage workers.

This creates a polarization problem.

McKinsey projects that by 2030, Europe and the United States will each need approximately 12 million occupational transitions. That is double the pre-pandemic pace. In the US, 30% of current work hours could be automated. In Europe, 27%.

The OECD examined wage data from 2014 to 2018. They found something unexpected: AI had not increased the wage gap between high-wage and low-wage occupations. In fact, wage inequality declined more in occupations most exposed to AI — like Business Professionals and Managers.

How can this be?

Because AI reduces productivity differences within occupations. The gap between top performers and average performers shrinks. This is good for within-occupation inequality.

But it does not solve the between-occupation problem. It does not help the worker whose entire occupation disappears.

Where Institutions Matter Most

The difference between AI amplifying inequality and AI reducing it comes down to institutional structure.

Let me show you what I mean.

In the OECD case studies from 2023, researchers looked at how companies in manufacturing and finance implemented AI. The results varied dramatically based on how firms structured the implementation.

In manufacturing, companies using AI for quality assurance and predictive maintenance saw job reorganization — not job displacement. Workers who previously did manual inspections now oversee AI systems. They handle exceptions. Their work is safer and less tedious. But in some cases, work intensity increased. Performance targets went up. Stress levels rose.

What made the difference?

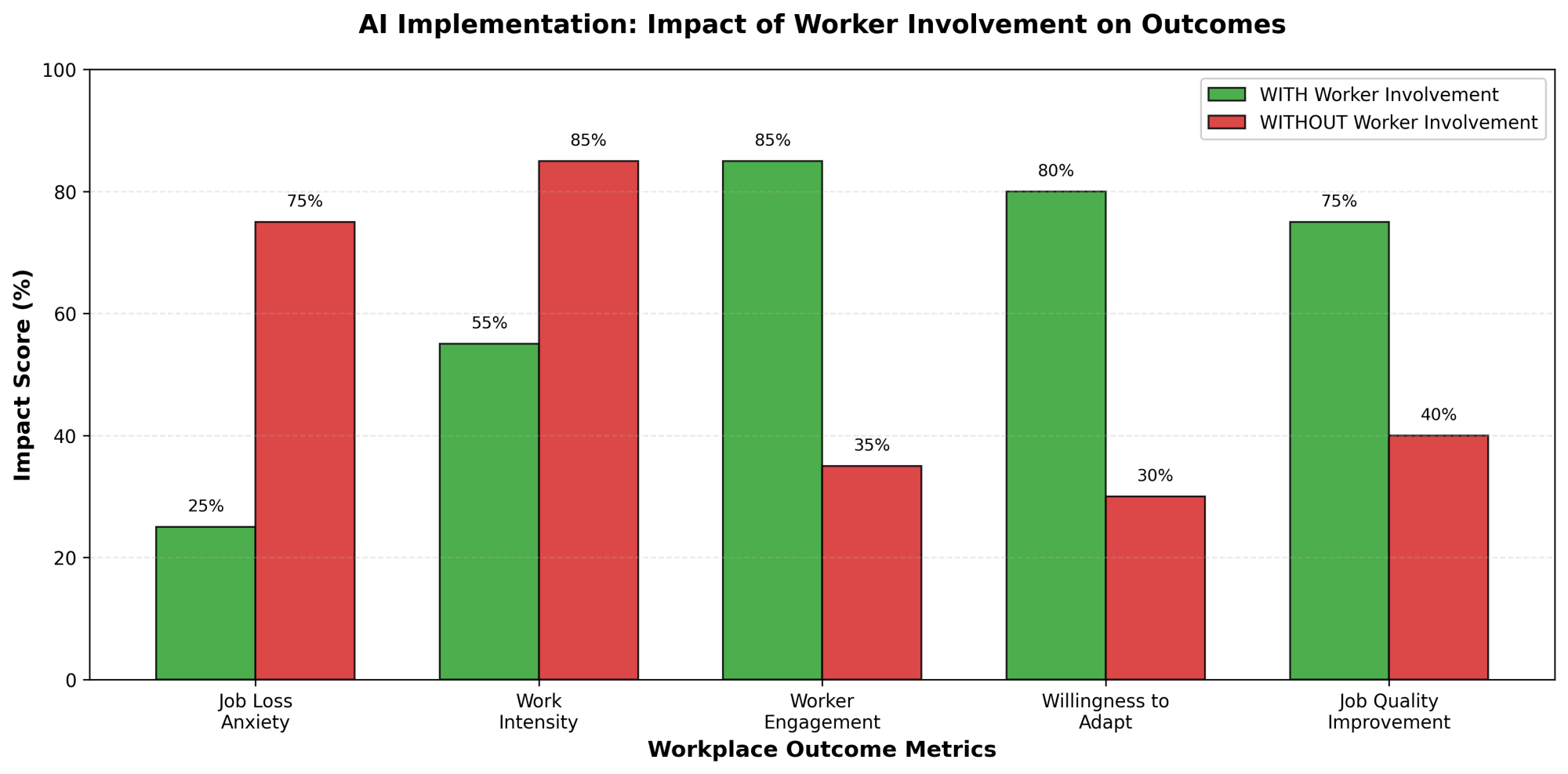

Worker involvement in the AI implementation process.

When workers participated directly in developing and deploying AI systems, job loss anxiety decreased. Willingness to engage with new technology increased. The OECD documented this pattern across multiple case studies.

In finance, AI is being used for fraud detection, chatbots, data analysis. Again, the impact on employment levels has been limited. But the quality of work changed. Employees freed from repetitive tasks could focus on more complex and engaging work. This happened when companies invested in reskilling and upskilling.

The London Stock Exchange Group implemented an AI-powered service. Query resolution times dropped by 50%. Swiss Federal Railways used AI for visual inspection of train components. Inspection times fell by 60%, errors by 20-30%

These are institutional choices. Not technological inevitabilities.

The New Economic Model

Something bigger is happening.

AI is not just changing jobs. It is changing the structure of the economy itself.

The numbers tell the story. UNCTAD projects the global AI market will grow from $189 billion in 2023 to $4.8 trillion by 2033. That is 25 times growth in ten years.

The IMF forecasts AI could expand global GDP by nearly 4% over the next decade in a high-growth scenario. Companies leading in AI adoption already outperform their peers by 15% in revenue generation. By 2026, this gap is projected to more than double.

But adoption is uneven. While 65% of organizations report using generative AI in at least one function, 74% report challenges in scaling AI across the enterprise. The World Economic Forum documented this in 2025.

The new economic model prioritizes several things:

First, data as an asset. In the AI-driven economy, data is not a byproduct. It is the foundational resource. Companies that can collect, manage, and analyze vast datasets effectively have a structural advantage.

Second, the digital core. A strong digital core — secure data, connected systems, open architecture — is now a prerequisite for competitiveness. Not an advantage. A requirement.

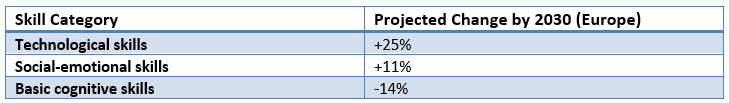

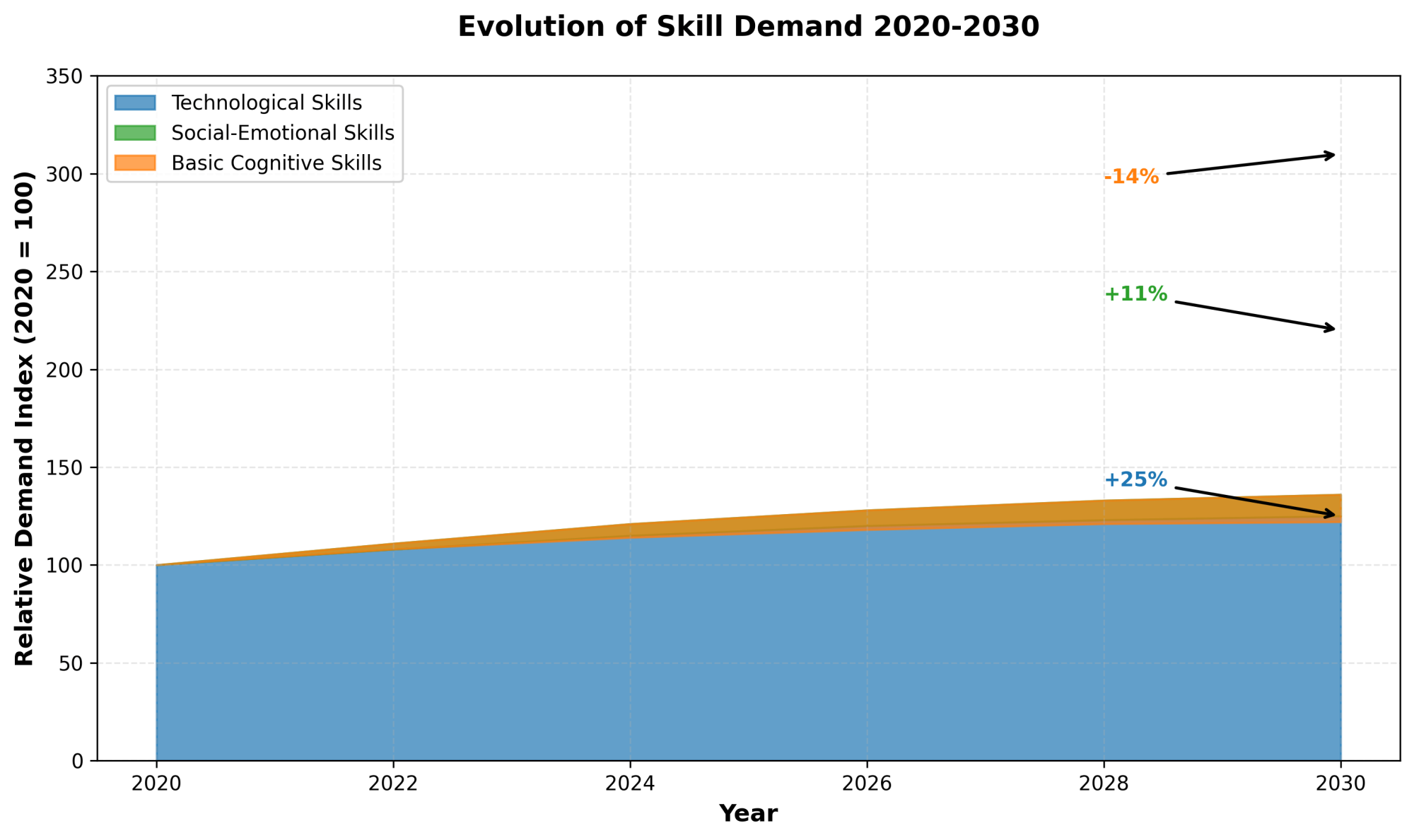

Third, fusion skills. The McKinsey Global Institute projects that by 2030, demand for technological skills in Europe will increase by 25%. Social-emotional skills will rise by 11%. But demand for basic cognitive skills could decline by 14%. This is a fundamental shift in what the labor market values.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute (2024)

Fourth, platform dynamics. AI is supercharging the platform economy through hyper-personalization and optimized logistics. Mojang Studios processes player sentiment data 66% faster using AI, allowing it to tailor experiences for millions of Minecraft players.

Real Companies, Real Results

Let me give you concrete examples.

BMW Group introduced a platform with multiple generative AI agents across sales, supply chain, and marketing. The system provides real-time insights by intelligently selecting data sources. Productivity in corporate functions and on showroom floors increased by 30-40%.

A California-based wellness start-up launched an AI agent that reduced queries requiring human assistance by 78%. The company could focus resources on core operations instead of routine customer service.

Beko, the home appliance manufacturer, developed a connected system of AI applications to overhaul its after-sales process. The system uses customer interaction data to predict issues, suggest upsell opportunities, and provide real-time troubleshooting guidance to technicians.

These companies are not experimenting. They are embedding AI deeply into core business functions.

Early adopters of generative AI tools are already achieving 2.4 times greater productivity and cost savings of 13%. The World Economic Forum documented this pattern across sectors in 2025.

The Global Divide Is Widening

Now we come to the most troubling part.

The benefits of AI are concentrating in advanced economies. This is not an accident. It is structural.

The IMF warns that AI will likely exacerbate cross-country income inequality. Advanced economies are projected to realize up to twice the income gains of low-income countries.

Why?

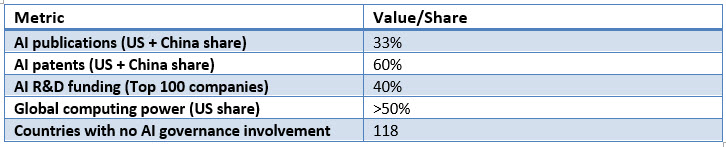

Three reasons: AI exposure, AI preparedness, and AI access.

AI exposure: Advanced economies have a higher share of jobs and sectors where AI can be applied productively.

AI preparedness: They have stronger digital infrastructure, better human capital, more developed regulatory frameworks.

AI access: They have availability of advanced hardware and essential data.

Even if low-income countries improve their preparedness — and they should — the IMF concludes these policy interventions are unlikely to fully eliminate the disparities.

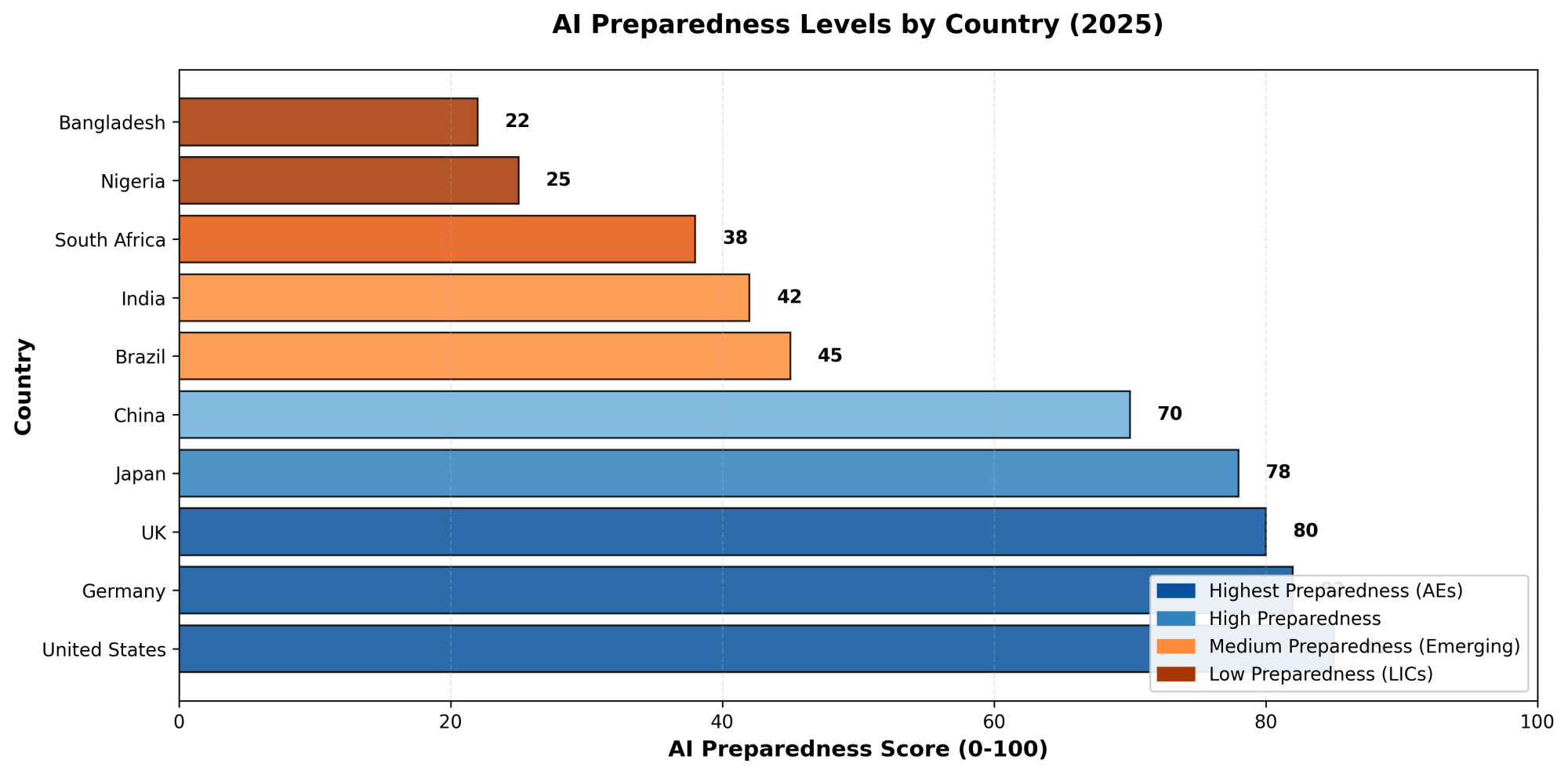

Consider the concentration of AI development. UNCTAD reports that the United States and China account for 33% of AI publications and 60% of AI patents. Just 100 top companies funded 40% of AI research and development in 2022. The US holds over half of the world’s global computing power.

As of 2025, 118 countries — mostly from the developing world — have no involvement in major AI governance initiatives.

This concentration gives a few nations and corporations immense influence over the trajectory of AI development and governance. The power dynamics are shifting. Not in favor of the global south.

Source: UNCTAD (2025)

Long-Term Investment Changes Everything

So what is the solution?

It starts with long-term investment. Not just in AI technology itself, but in the institutional structures that determine how AI affects society.

Governments need comprehensive social safety nets. Retraining programs for vulnerable workers. Investment in education systems that build digital skills from early ages. The World Bank points out that human capital levels are much lower in low and middle-income countries, which limits their ability to work effectively with AI.

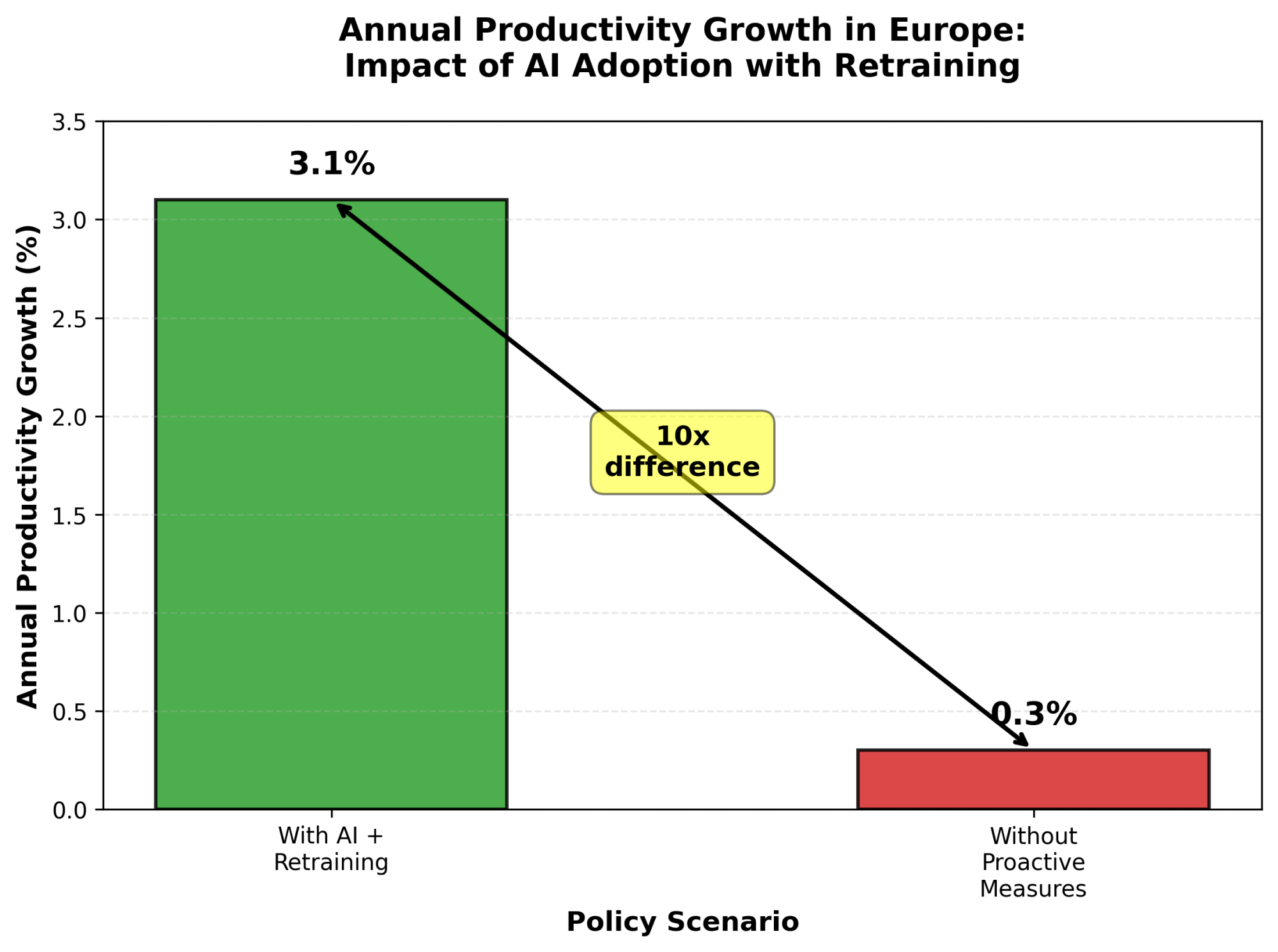

McKinsey estimates that rapid AI adoption combined with proactive workforce retraining could unlock 3.1% annual productivity growth in Europe. Without such measures, the growth rate might be only 0.3%.

That is a factor of ten difference.

Corporate governance matters too. The way firms implement AI is critical. Direct worker involvement in AI development and implementation reduces job loss anxiety. It improves workers’ willingness to engage with new technologies. The OECD case studies prove this.

On the international level, inclusive governance frameworks are urgently needed. The development and deployment of AI must be guided by principles of fairness, transparency, and shared prosperity. Right now, most of the developing world has no seat at the table.

WIMFhat We Will See Next

The coming years are pivotal.

We will see if AI becomes a force for equitable progress or a driver of deeper global division.

Here is what to watch:

First, the pace of occupational transitions. Are countries investing in large-scale retraining programs? Or are displaced workers left to navigate the transition alone? Second, the evolution of within-firm inequality. Do companies that adopt AI see wage compression or wage polarization? The OECD found that AI reduced within-occupation inequality between 2014 and 2018. Will this pattern hold?

Third, the global preparedness gap. Are low and middle-income countries building digital infrastructure and human capital fast enough? The World Bank’s exposure scores show a clear gap. Is it widening or narrowing?

Fourth, corporate adoption patterns. Which sectors move from experimentation to enterprise-wide integration? Currently, 74% of organizations struggle to scale AI. This will change.

Fifth, governance frameworks. Will developing countries gain meaningful participation in AI governance? Or will the concentration of power persist?

The answers to these questions will determine whether AI amplifies or reduces labor inequality.

The Choice Is Institutional

AI does not have inherent effects on labor inequality.

The effects depend on institutional structures. On policy choices. On how companies implement the technology. On whether workers have a voice in the process.

The economic model is changing. Data is now a foundational asset. Fusion skills are replacing basic cognitive skills. Platform dynamics are accelerating. The productivity gains are real — companies leading in AI adoption are already outperforming peers by 15%, and this gap will double by 2026.

But these gains are not distributed equally. Between countries, between sectors, between occupations, between workers.

The IMF projects that advanced economies will realize twice the income gains of low-income countries from AI. McKinsey shows that low-wage workers face redeployment risks 3 to 14 times higher than high-wage workers. UNCTAD documents that 118 countries have no involvement in AI governance.

These are not inevitable outcomes. They are the results of current institutional structures.

Change the structures, and you change the outcomes.

The question is not whether AI will affect labor inequality. It will.

The question is: Do our institutions amplify or reduce that inequality?

The choice is ours.

References

Cazzaniga, M., et al. (2024). Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/2024/001.

Demombynes, G., Langbein, J., & Weber, M. (2025). The Exposure of Workers to Artificial Intelligence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 11057.

Ellingrud, K., et al. (2023). Generative AI and the future of work in America. McKinsey Global Institute.

Green, A. (2024). Artificial intelligence and the changing demand for skills in the labour market. OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers, No. 14.

Hazan, E., et al. (2024). A new future of work: The race to deploy AI and raise skills in Europe and beyond. McKinsey Global Institute.

Heimberger, H., Horvat, D., & Schultmann, F. (2024). Exploring the factors driving AI adoption in production: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Information Technology and Management.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). The Global Impact of AI: Mind the Gap. IMF Working Paper.

Milanez, A. (2023). The impact of AI on the workplace: Evidence from OECD case studies of AI implementation. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 289.

OECD. (2024). What impact has AI had on wage inequality?

Rockall, E., Tavares, MM ve Pizzinelli, C. (2025). Yapay Zeka Benimsenmesi ve Eşitsizlik. IMF Çalışma Belgesi WP/25/68.

Soulami, M., Benchekroun, S., & Galiulina, A. (2024). Yapay zekanın işyerinde benimsenmesinin çalışanları nasıl etkilediğini araştırmak: bibliyometrik ve sistematik bir inceleme. Yapay Zeka Alanındaki Sınırlar, 7.

UNCTAD. (2025). Teknoloji ve İnovasyon Raporu 2025: Kalkınma için kapsayıcı yapay zeka.

Dünya Ekonomik Forumu. (2025). Yapay Zeka Uygulamada: Endüstriyi Dönüştürmek İçin Denemelerin Ötesinde.